Integrating Liver Non‑Parenchymal Cells into Preclinical Toxicology Models

What Are Liver Non‑Parenchymal Cells and How Do They Differ from Hepatocytes?

Liver non-parenchymal cells (NPCs) are a heterogeneous group of cells that form the non-hepatocyte component of the liver, accounting for approximately 30% of total liver cells. They play essential roles in immune regulation, vascular function, tissue repair, and disease progression.

Non‑parenchymal cells include distinct cell types:

- Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs): Line the sinusoids with a fenestrated structure lacking a basement membrane, which allows exchange of solutes between the blood and hepatocytes. They clear macromolecules from circulation through endocytosis. This cell type is also coinvolved in immune responses by capturing and presenting antigens to immune cells, such as Kupffer cells.

- Kupffer cells: Also known as the resident macrophages of the liver, they are in charge of removing pathogens, dead cells, and toxins. They secrete cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, thereby coordinating immune and inflammatory responses.

- Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs): Normally store vitamin A in lipid droplets but, upon activation, produce extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen, that lead to fibrosis during chronic injury.

- Liver‑associated lymphocytes and biliary epithelial cells contribute to immune surveillance and bile duct maintenance and modification, respectively.

NPCs differ from hepatocytes in their function, structure, origin, and proportion, but their interaction is essential to develop and maintain liver functions.

Hepatocytes are the main cellular component of the liver, accounting for two-thirds of the total cell population. They are the primary metabolic workhorses of the organ responsible for detoxification, protein synthesis, and bile production. While NPCs present a mesoderm-derived origin (except for cholangiocytes), hepatocytes differentiate from the endoderm during embryonic development. Their characteristic polygonal morphology stands out in contrast to the diverse morphologies of NPCs (fenestrated, stellate, macrophage-like).

Integrating Non‑Parenchymal Cells into In Vitro Toxicology Assays

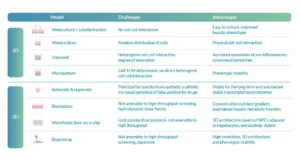

Preclinical liver models, which include NPCs, encompass a wide range of culture systems varying in complexity, dimensionality, and physiological relevance (Figure 1).

Two-dimensional (2D) static cultures are among the simplest methods and include monocultures, mixed cocultures, transwell, and micropatterned formats. These systems are simple to establish, allow for basic cell growth and interaction studies, but lack the three-dimensional architecture and dynamic environment of the liver in vivo.

Figure 1. Co-culture models. Adapted from: Stern S, Wang H, Sadrieh N. Microphysiological Models for Mechanistic-Based Prediction of Idiosyncratic Drug-induced Liver Injury (DILI). Cells. 2023 May 25;12(11):1476

In contrast, three-dimensional (3D) models, including scaffold-free and scaffold spheroids, organoids, bioprinting, microfluidic liver-on-a-chip, and perfusion-based bioreactors, provide a more realistic representation of liver tissue architecture and microenvironment. These models enable long-term viability, stable gene expression, and functional metabolic activity, as well as controlled nutrient and oxygen gradients. Perfusion systems and microfluidic devices further simulate blood flow and shear stress, enhancing cellular functionality and intercellular communication.

Enhancing DILI Models with Non‑Parenchymal Cell Co‑cultures

3D models, such as spheroids, are gaining momentum as drug-induced liver injury (DILI) models in drug discovery and development.

Introducing NPCs into spheroids, together with primary human hepatocytes, increases CYP activity and urea secretion compared to spheroids with hepatic cells alone. Although 3D spheroid cultures of hepatocytes can be cultured in the long term and maintain stable transcriptomes and proteomes, they display reduced expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters. Messner et al. observed a reduction of CYP2C8 and CYP2E1 expression after 35 days of culture.

3D conformation also increases predictive values and sensitivity for drugs that elicit hepatotoxicity. The addition of Kupffer cells and LSECs in a 3D spheroid model enhances the sensitivity to identify hepatotoxic drugs compared to a 2D primary hepatocyte monoculture. Proctor et al. tested a panel of 110 marketed drugs using this model, where 63% of them were associated with DILI, demonstrating that spheroids outperformed PHH monocultures in differentiating hepatotoxicants from different classes. Co-culture spheroids have also demonstrated increased sensitivity to acetaminophen-induced toxicity compared to primary hepatocyte spheroids.

Co-culture spheroids are not the only cell culture model that enhances primary hepatocytes’ sensitivity to assess DILI. Microfluidic liver-chip technologies enable dynamic 3D co-culture of PHHs and NPCs with controlled perfusion, enhancing longevity and physiologic function of cultures and yielding improved prediction of DILI, including immune-related mechanisms. Ewart et al. evaluated the predictive power of Emulate LiverChip by seeding PHH and LSECs in a 1:1 ratio. They identified 12 out of 15 hepatotoxic drugs and did not falsely identify any nonhepatotoxic drugs.

Challenges and Considerations When Working with NPCs in Preclinical Models

Establishing reliable NPCs liver co-culture models presents multiple challenges related to the complexity of cellular interactions and the balance between physiological relevance and experimental practicality (Table 1).

In 2D systems, monocultures combined with soluble fractions lack direct cell–cell communication, despite being simple to culture and improving the hepatic phenotype compared to monocultures alone. Mixed cultures offer physical interactions between cells but suffer from random cell distribution, leading to inconsistencies. Transwell systems, on the other hand, introduce heterogeneous cell–cell interactions and variable separation, which, although useful for studying inflammatory responses, limit control over experimental conditions. Micropatterned cultures improve phenotypic stability but lose direct heterogeneous interactions and may experience detachment from the extracellular matrix.

Table 1. Advantages and challenges with establishing NPC–liver-co-culture. Adapted from: Stern S, Wang H, Sadrieh N. Microphysiological Models for Mechanistic-Based Prediction of Idiosyncratic DILI. Cells. 2023 May 25;12(11):1476

In 3D systems, spheroids and organoids provide stable and long-term models that better replicate tissue structure, yet synthetic scaffolds can introduce toxicity and false positives during drug testing. Bioreactors recreate metabolic gradients and hepatic function but are limited by shear stress and incompatibility with high-throughput screening. Microfluidic liver-on-a-chip models closely mimic in vivo architecture, incorporating multiple cell layers and extracellular matrix components, though the lack of standardized protocols and scalability remains an obstacle. Finally, bioprinting enables precise 3D architectures and phenotypic stability but faces cost and throughput limitations, highlighting the ongoing trade-off between physiological relevance and experimental feasibility.

The choice of model depends largely on the specific research question, balancing physiological relevance with practical considerations like cost and experimental throughput. Understanding these differences is critical when integrating non-parenchymal cells (NPCs) into preclinical toxicology models, where their functional contribution can significantly improve the predictive power for human liver toxicology.

References

Ewart L, Apostolou A, Briggs SA, Carman CV, Chaff JT, Heng AR, Jadalannagari S, Janardhanan J, Jang KJ, Joshipura SR, Kadam MM, Kanellias M, Kujala VJ, Kulkarni G, Le CY, Lucchesi C, Manatakis DV, Maniar KK, Quinn ME, Ravan JS, Rizos AC, Sauld JFK, Sliz JD, Tien-Street W, Trinidad DR, Velez J, Wendell M, Irrechukwu O, Mahalingaiah PK, Ingber DE, Scannell JW, Levner D. Performance assessment and economic analysis of a human Liver-Chip for predictive toxicology. Commun Med (Lond). 2022 Dec 6;2(1):154. doi: 10.1038/s43856-022-00209-1.

Messner S, Fredriksson L, Lauschke VM, Roessger K, Escher C, Bober M, Kelm JM, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Moritz W. Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Functional Long-Term Characterization of Multicellular Three-Dimensional Human Liver Microtissues. Appl In Vitro Toxicol. 2018 Mar 1;4(1):1-12. doi: 10.1089/aivt.2017.0022.

Proctor WR, Foster AJ, Vogt J, Summers C, Middleton B, Pilling MA, Shienson D, Kijanska M, Ströbel S, Kelm JM, Morgan P, Messner S, Williams D. Utility of spherical human liver microtissues for prediction of clinical drug-induced liver injury. Arch Toxicol. 2017 Aug;91(8):2849-2863. doi: 10.1007/s00204-017-2002-1.

Seo W, Jeong WI. Hepatic non-parenchymal cells: Master regulators of alcoholic liver disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Jan 28;22(4):1348-56. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1348.

Stern S, Wang H, Sadrieh N. Microphysiological Models for Mechanistic-Based Prediction of Idiosyncratic DILI. Cells. 2023 May 25;12(11):1476. doi: 10.3390/cells12111476.